Research News

-

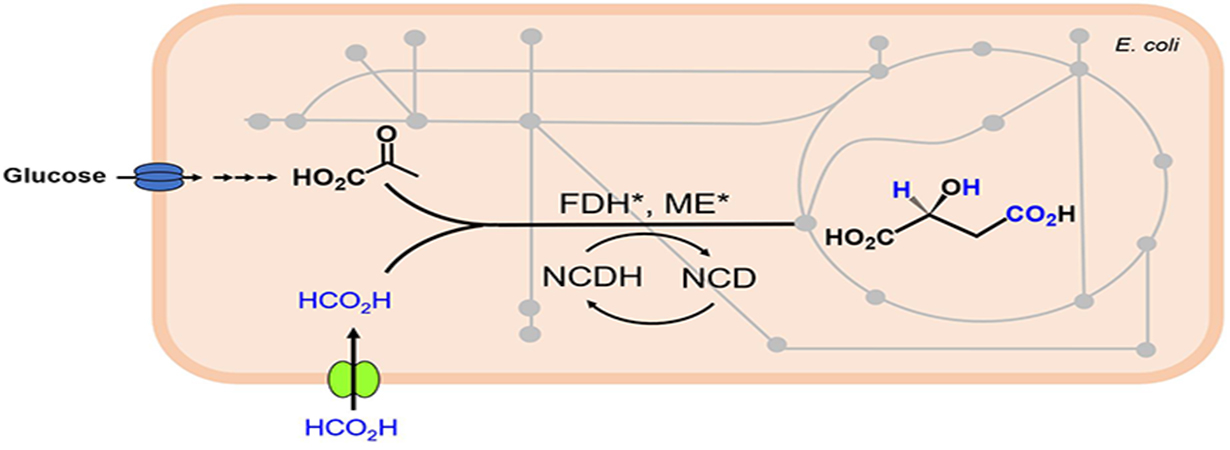

01 08, 2020Pathway-selectively energy transfer system was constructedScientists made a new progress in the research of non-natural cofactor. Researchers successfully constructed a non-natural cofactor and formate driven system with pathway-selective energy transfer. This work was published in Angewandte Chemie International Edition.Recently, Biomass Conversion Technology Group led by Prof. ZHAO Zongbao from Dalian Institute of Chemical Physics (DICP) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) made a new progress in the research of non-natural cofactor. Researchers successfully constructed a non-natural cofactor and formate driven system with pathway-selective energy transfer. This work was published in Angewandte Chemie International Edition. Nicotinamide adenosine dinucleotide (NAD) and its reduced form are linked to hundreds of cellular reactions, and fluctuation of NAD(H) level causes global disturbance to cellular metabolism. To over come the limitations of the regulation of natural cofactors, the group led by Prof. ZHAO Zongbao has been working on the research area of non-natural cofactors. In previous works, bioorthogonal redox catalytic system was constructed with non-natural cofactor dependent oxidoreductase mutants via directed revolution (J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2011, 133, 20857). In addition, cofactor preference of phosphite dehydrogenase was engineered and the molecular basis of cofactor preference was elucidated (ACS Catal., 2019, 9, 1883). Moreover, researchers also constructed non-natural organic acids synthesis system driven by phosphite, selectively transferring energy to the metabolic pathways of bacteria (ACS Catal., 2017, 7, 1977). In this work, a nicotinamide cytosine dinucleotide (NCD) dependent formate dehydrogenase (FDH*) was obtained through directed evolution, and new bioorthogonal system was built with NCD dependent FDH* and malic enzyme (ME*). Results showed that pyruvate was reductive carboxylated with carbon unit and reducing power from formate. Further, researchers constructed a malate synthesis system driven by formate and NCD in microbe. This work reversed the natural direction of metabolic node of malate, showing great value for redesign of metabolic pathways and selectively regulation the substance and energy metabolism.

01 08, 2020Pathway-selectively energy transfer system was constructedScientists made a new progress in the research of non-natural cofactor. Researchers successfully constructed a non-natural cofactor and formate driven system with pathway-selective energy transfer. This work was published in Angewandte Chemie International Edition.Recently, Biomass Conversion Technology Group led by Prof. ZHAO Zongbao from Dalian Institute of Chemical Physics (DICP) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) made a new progress in the research of non-natural cofactor. Researchers successfully constructed a non-natural cofactor and formate driven system with pathway-selective energy transfer. This work was published in Angewandte Chemie International Edition. Nicotinamide adenosine dinucleotide (NAD) and its reduced form are linked to hundreds of cellular reactions, and fluctuation of NAD(H) level causes global disturbance to cellular metabolism. To over come the limitations of the regulation of natural cofactors, the group led by Prof. ZHAO Zongbao has been working on the research area of non-natural cofactors. In previous works, bioorthogonal redox catalytic system was constructed with non-natural cofactor dependent oxidoreductase mutants via directed revolution (J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2011, 133, 20857). In addition, cofactor preference of phosphite dehydrogenase was engineered and the molecular basis of cofactor preference was elucidated (ACS Catal., 2019, 9, 1883). Moreover, researchers also constructed non-natural organic acids synthesis system driven by phosphite, selectively transferring energy to the metabolic pathways of bacteria (ACS Catal., 2017, 7, 1977). In this work, a nicotinamide cytosine dinucleotide (NCD) dependent formate dehydrogenase (FDH*) was obtained through directed evolution, and new bioorthogonal system was built with NCD dependent FDH* and malic enzyme (ME*). Results showed that pyruvate was reductive carboxylated with carbon unit and reducing power from formate. Further, researchers constructed a malate synthesis system driven by formate and NCD in microbe. This work reversed the natural direction of metabolic node of malate, showing great value for redesign of metabolic pathways and selectively regulation the substance and energy metabolism.

Non-natural cofactor and formate driven reductive carboxylation of pyruvate. FDH*: formate dehydrogenase mutant; ME*: malic enzyme mutant; NCD: nicotinamide cytosine dinucleotide. (Image by GUO Xiaojia) This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China and Dalian Institute of Chemical Physics. (Text and image by GUO Xiaojia) -

01 02, 2020100 kWh Lead-Carbon Battery Energy Storage System developed by DICP is in OperationRecently, scientists have developed a 100 kWh lead-carbon battery energy storage system and successfully connected the system to the grid in Xinghai main capus of DICP.Recently, the research group led by Prof. LI Xianfeng and Prof. ZHANG Huamin from the Dalian Institute of Chemical Physics (DICP) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) have developed a 100 kWh lead-carbon battery energy storage system and successfully connected the system to the grid in Xinghai main capus of DIC. This system mainly provides stable power supply for DICP canteen load and realizes the dynamic balance between power supply, power grid, load, and energy storage, further promoting the development and industrialization of lead-carbon battery technology. The system consists of solar photovoltaic power generation module, lead carbon battery, grid-connected inverter, power metering system, battery management system, and remote monitoring system. It operates with grid-connected and off-grid mixed operation mode, which facilitates the consumption of renewable energy and provides additional power that is stored in electricity valley for peak load. Besides, the system can ensure the continuous power supply for canteen load and achieve the dynamic balance between power supply, power grid, load, and energy storage. Specifically, in the off-grid mode, solar photovoltaic power generation module gives priority to the canteen power supply, and the excess energy is used to charge the lead-carbon battery system. In the grid-connected mode, the power grid charges the battery system when the power demand is low. On the contrary, the battery system discharges its power to ensure canteen power supply during peak hours and abnormal operation of power grid.

01 02, 2020100 kWh Lead-Carbon Battery Energy Storage System developed by DICP is in OperationRecently, scientists have developed a 100 kWh lead-carbon battery energy storage system and successfully connected the system to the grid in Xinghai main capus of DICP.Recently, the research group led by Prof. LI Xianfeng and Prof. ZHANG Huamin from the Dalian Institute of Chemical Physics (DICP) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) have developed a 100 kWh lead-carbon battery energy storage system and successfully connected the system to the grid in Xinghai main capus of DIC. This system mainly provides stable power supply for DICP canteen load and realizes the dynamic balance between power supply, power grid, load, and energy storage, further promoting the development and industrialization of lead-carbon battery technology. The system consists of solar photovoltaic power generation module, lead carbon battery, grid-connected inverter, power metering system, battery management system, and remote monitoring system. It operates with grid-connected and off-grid mixed operation mode, which facilitates the consumption of renewable energy and provides additional power that is stored in electricity valley for peak load. Besides, the system can ensure the continuous power supply for canteen load and achieve the dynamic balance between power supply, power grid, load, and energy storage. Specifically, in the off-grid mode, solar photovoltaic power generation module gives priority to the canteen power supply, and the excess energy is used to charge the lead-carbon battery system. In the grid-connected mode, the power grid charges the battery system when the power demand is low. On the contrary, the battery system discharges its power to ensure canteen power supply during peak hours and abnormal operation of power grid.

100 kWh Energy Storage System of Lead-Carbon Batteries. (Image By YAN Jingwang)

Solar Panels on the Roof of the Dining Hall for Staff & Students. (Image by YAN Jingwang) DICP has cooperated with FENGFAN co., LTD. since 2015 and established the center of the joint research and development for advanced battery technology, dedicated to the research and development of the advanced technology of lead-carbon battery industrialization. Now, special carbon materials for lead-carbon battery with proprietary intellectual property rights and various models of lead-carbon battery prototype including 12 V/38 Ah, 12 V/150 Ah, and 2 V/1000 Ah have been developed. The series of lead-carbon batteries jointly developed by both sides have the advantages of long-cycle life, high rechargeable capacity, and low cost, thus showing an excellent application prospect in the field of energy storage.

Control Panel of the 100 kWh Energy Storage System of Lead-Carbon Batteries. (Image by YAN Jingwang) The project was supported by CAS Strategic Leading Science & Technology Program (A) "transformational clean energy key technologies and demonstration". (Text by YAN Jingwang) -

12 30, 2019Scientists Reveal Structure Transformation of Water in Alcohol-Water SolutionsScientists from the Dalian Institute of Chemical Physics (DICP) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences and Peking University revealed ordered to disordered transformation of enhanced water structure on hydrophobic surfaces in concentrated alcohol-water solutions. The research was published in Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters.

12 30, 2019Scientists Reveal Structure Transformation of Water in Alcohol-Water SolutionsScientists from the Dalian Institute of Chemical Physics (DICP) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences and Peking University revealed ordered to disordered transformation of enhanced water structure on hydrophobic surfaces in concentrated alcohol-water solutions. The research was published in Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters.

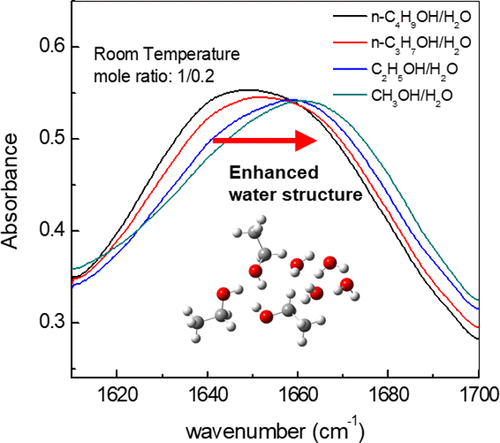

Scientists from the Dalian Institute of Chemical Physics (DICP) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences and Peking University revealed ordered to disordered transformation of enhanced water structure on hydrophobic surfaces in concentrated alcohol-water solutions. The research was published in Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters.

The effects of hydrophobic solutes on the structure of the surrounding water have been a topic of debate for almost 70 years. However, a consistent description of the physical insight into the causes of the anomalous thermodynamic properties of alcohol-water mixtures is lacking.

This work employed the temperature-dependent FTIR spectroscopy combined with the femtosecond infrared spectroscopy to explore the water structural transformation in concentrated alcohol-water solutions.

Experiments show that the enhancement of water structure arises around micro-hydrophobic interfaces at room temperature in the solutions. As temperature increases, this ordered water structure disappears and a surface topography dependent new disordered water structure arises at concentrated solutions of large alcohols. A more-ordered-than-water structure can transform into a less-ordered-than-water structure.

Effect of alcohol size on water structural transformation in concentrated alcohol-water solutions. (Image by YUAN Kaijun)

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, and the Chemical Dynamics Research Center. (Text by YUAN Kaijun)

-

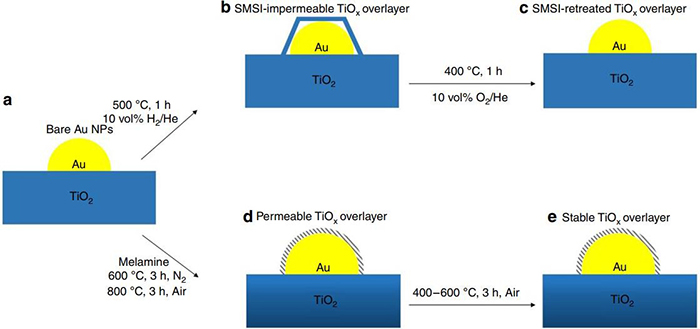

12 28, 2019Ultrastable Au nanoparticles on titania achieved by an encapsulated strategy under oxidative atmosphere induced by melamineScientists recently reported the produce of ultrastable Au nanoparticles on titania achieved by an encapsulated strategy under oxidative atmosphere induced by melamine. This work was recently published as a highlight paper on Nature Research Chemistry Community.The group of Prof. WANG Junhu from the Dalian Institute of Chemical Physics (DICP) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) recently reported the produce of ultrastable Au nanoparticles on titania achieved by an encapsulated strategy under oxidative atmosphere induced by melamine.This work was recently published on Nat. Conmun. and highlighted on Nature Research Chemistry Community. Supported gold catalysts play an important role in many catalytic reactions, such as CO oxidation, water-gas shift (WGS) reaction and oxidative reforming of methane. However, Au nanoparticles (NPs) are tending to sinter at high temperature because of its low Tammann temperature, resulting in poor on-stream stability. Strong metal-support interaction (SMSI), an important concept in heterogeneous catalysis, has been studied extensively since it was termed by Tauster et al. in the late 1970s. The classical SMSI was widely found for platinum group metals supported on reducible oxides, such as TiO2 and CeO2, upon high-temperature reduction pretreatment. However, unlike platinum group metals, it has been well-recognized for a long time that Au cannot manifest SMSI due to its low work function and low surface energy. In 2017, we demonstrated the existence of classical SMSI between Au and TiO2 for the first time and the encapsulation of Au by TiOx overlayer was also observed (Sci Adv., 2017, 3, e1700231). Whereas SMSI state is reversible that the formed TiOx overlayer will retreat under further oxidation pretreatment at high temperature (>400 oC), leading to invalid effect on the catalytic performance of the gold. Therefore, it is urgent to develop new strategy to construct an overlayer containing Ti species on Au, which is endurable under oxidative atmosphere.

12 28, 2019Ultrastable Au nanoparticles on titania achieved by an encapsulated strategy under oxidative atmosphere induced by melamineScientists recently reported the produce of ultrastable Au nanoparticles on titania achieved by an encapsulated strategy under oxidative atmosphere induced by melamine. This work was recently published as a highlight paper on Nature Research Chemistry Community.The group of Prof. WANG Junhu from the Dalian Institute of Chemical Physics (DICP) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) recently reported the produce of ultrastable Au nanoparticles on titania achieved by an encapsulated strategy under oxidative atmosphere induced by melamine.This work was recently published on Nat. Conmun. and highlighted on Nature Research Chemistry Community. Supported gold catalysts play an important role in many catalytic reactions, such as CO oxidation, water-gas shift (WGS) reaction and oxidative reforming of methane. However, Au nanoparticles (NPs) are tending to sinter at high temperature because of its low Tammann temperature, resulting in poor on-stream stability. Strong metal-support interaction (SMSI), an important concept in heterogeneous catalysis, has been studied extensively since it was termed by Tauster et al. in the late 1970s. The classical SMSI was widely found for platinum group metals supported on reducible oxides, such as TiO2 and CeO2, upon high-temperature reduction pretreatment. However, unlike platinum group metals, it has been well-recognized for a long time that Au cannot manifest SMSI due to its low work function and low surface energy. In 2017, we demonstrated the existence of classical SMSI between Au and TiO2 for the first time and the encapsulation of Au by TiOx overlayer was also observed (Sci Adv., 2017, 3, e1700231). Whereas SMSI state is reversible that the formed TiOx overlayer will retreat under further oxidation pretreatment at high temperature (>400 oC), leading to invalid effect on the catalytic performance of the gold. Therefore, it is urgent to develop new strategy to construct an overlayer containing Ti species on Au, which is endurable under oxidative atmosphere.

SMSI and melamine-induced TiOx overlayer structure and behavior. (a) Bare Au nanoparticles on TiO2. (b) Au/TiO2 catalyst that forms an impermeable SMSI TiOx overlayer after treatment with 10 vol% H2/He at 500 oC. (c) SMSI TiOx overlayer retreats when exposed to oxidation condition at 400 oC which is almost similar with that in (a). (d) Melamine-modified catalyst that forms a permeable TiOx overlayer after treatment with N2 at high temperature (600 oC) followed by treatment with air at 800 oC. (e) Stable melamine-induced TiOx overlayer under air condition modifies the Au NPs catalytic bahavior. (Image by LIU Shaofeng) Here, we reported that Au NPs can be encapsulated by a permeable TiOx overlayer under oxidative atmosphere, the reverse of the condition required for classical SMSI. We found that the key to construct the above cover layer is the application of melamine and pretreatment in nitrogen condition, followed by calcination at 800 oC in air atmosphere. More importantly, this TiOx overlayer is stable upon further calcination under oxidation condition, which is contrary to the classical SMSI. In order to confirm the valance of the Ti species, electron energy loss spectroscopy (EELS) was examined and it was found that the Ti species existed as Ti3+ oxidation state, in consistent with the classical SMSI. And X-ray adsorption spectroscopy was also employed to investigate whether new bond was formed and the fitting results revealed that new Au-Ti bond was formed when the encapsulation occurred. Owing to the formation of the overlayer, the resultant catalyst is resistant to sintering and exhibits high activity as well excellent durability in WGS reaction and simulated practical testing. Moreover, this original strategy can be extended to colloidal Au supported on TiO2 and commercial gold catalyst named RR2Ti. We believe these new findings provide a new avenue to rationally devise and develop highly stable Au catalysts with controllable activity. This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China and the International Partnership Program of Chinese Academy of Sciences. It was dedicated to the 70th anniversary of DICP, CAS.(Text by LIU Shaofeng) -

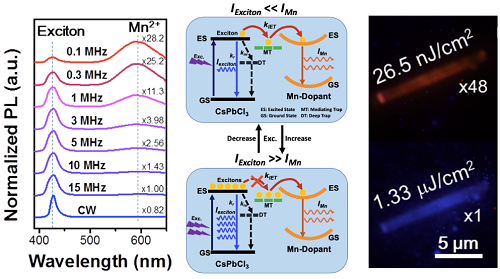

12 28, 2019Scientists Reveal Emission Color Tuning from an Individual Mn-Doped Perovskite MicrocrystalScientists recently reported the excitation-dependent PL tunability from an individual Mn2+ doped CsPbCl3 perovskite microcrystal (MC), realizing a continuous, reversible, wide-range and stable emission color tuning. This work was recently published on J. Am. Chem. Soc.The group of Prof. JIN Shengye from the Dalian Institute of Chemical Physics (DICP) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) recently reported the excitation-dependent PL tunability from an individual Mn2+ doped CsPbCl3 perovskite microcrystal (MC), realizing a continuous, reversible, wide-range and stable emission color tuning. This work was recently published on J. Am. Chem. Soc.

12 28, 2019Scientists Reveal Emission Color Tuning from an Individual Mn-Doped Perovskite MicrocrystalScientists recently reported the excitation-dependent PL tunability from an individual Mn2+ doped CsPbCl3 perovskite microcrystal (MC), realizing a continuous, reversible, wide-range and stable emission color tuning. This work was recently published on J. Am. Chem. Soc.The group of Prof. JIN Shengye from the Dalian Institute of Chemical Physics (DICP) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) recently reported the excitation-dependent PL tunability from an individual Mn2+ doped CsPbCl3 perovskite microcrystal (MC), realizing a continuous, reversible, wide-range and stable emission color tuning. This work was recently published on J. Am. Chem. Soc.

PL spectra, exciton dynamics illustration and PL images of Mn-Doped CsPbCl3 MC. (Image by SUN Qi)

CsPbX3 (X=Cl-, Br-, I-) perovskites exhibit great application potentials in light-emitting devices because of their stable physical and chemical properties, high PL quantum yield and continuously adjustable band structures, etc. Previously, researches on the regulation of emission color of perovskites are mainly focusing on controlling the particle size of nanocrystals and adjusting the types and relative proportions of halogen ions. However, among these materials, the fluorescence emission wavelength corresponds to their structures and compositions therefore it is required to change the composition of materials or use multiple kinds of material for emission color tuning, which is inconvenient to practical applications. The group for the first time reported the synthesis of Mn2+ doped CsPbCl3 MCs showing dual-color PL emission from exciton (blue) and Mn2+ (orange). The obtained Mn2+ doped CsPbCl3 MCs show a continuous, reversible and wide-range excitation-dependent color tuning without changing the chemical composition of materials. Transient spectroscopy and temperature-dependent PL measurements confirmed that the exciton-to-dopant internal energy transfer (IET) in Mn2+ doped CsPbCl3 MCs is mediated by some shallow trap states, rather than through a direct transfer pathway. Therefore, the saturation of Mn2+ emission is caused by a bottlenecked energy transfer effect by saturating the mediating trap states at high excitation intensities. The Mn2+ doped MCs also exhibit a high photo-stability on the reversible switch of emission color between orange and blue for more than 300 cycles within a continuous operation time of 14 h. In view of the stable and color-switchable emission properties, Mn2+ doped perovskite MCs may find applications in nanophotonic devices with using a single MC. This work is financially supported by the NFSC, the MOST, and the Strategic Priority Research Program of Chinese Academy of Sciences. (Text by SUN Qi) -

12 27, 2019DICP Scientists Develop Nanochannels Device for Precise Discrimination of Sialylated Glycan Linkage isomersScientists recently constructed a bioinspired nanochannel device and realized the precise recognition and discrimination of sialylated glycan linkage isomers. This work was published in Chemical Science.

12 27, 2019DICP Scientists Develop Nanochannels Device for Precise Discrimination of Sialylated Glycan Linkage isomersScientists recently constructed a bioinspired nanochannel device and realized the precise recognition and discrimination of sialylated glycan linkage isomers. This work was published in Chemical Science.

A research group led by Prof. QING Guangyan from the Dalian Institute of Chemical Physics (DICP) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) recently constructed a bioinspired nanochannel device and realized the precise recognition and discrimination of sialylated glycan linkage isomers. This work was published in Chemical Science.

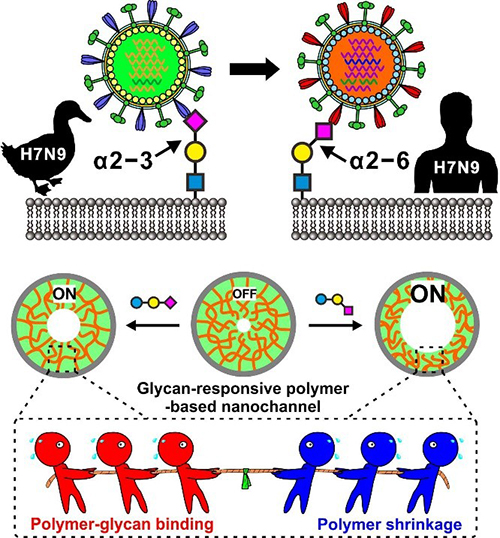

Design of the biomimetic nanochannels for glycan recognition. (A) H7N9 virus binds to avian a2–3-linked sialylated glycan receptor, while the reassortant H7N9 virus binds to human a2–6-linked glycan receptor. (B) Schematic illustration of glycan-induced nanochannel“OFF–ON”changes and

the tug-of-war cartoon to illustrate the competition between polymer-glycan binding and the polymer shrinkage. (Image by LI Minmin)

Sialylated glycans that are attached to cell surface mediate diverse cellular processes such as immune responses, pathogen binding, and cancer progression. Precise determination of sialylated glycans, particularly their linkage isomers that can trigger distinct biological events and are indicative of different cancer types, remains a challenge, due to their complicated composition and limited structural differences.

In this work, QING and co-workers creatively introduced the bioinspired nanochannel as its sensitive perturbation of ion flux to the recognition of glycans with subtitle difference in structure. They report a glycan-responsive polymer-modified nanochannels device, which demonstrates the capacity of recognizing and discriminating sialic acid form other neutral monosaccharides, different sialic acids, and even sialylated glycans with α2-3 and α2-6 linkage.

In-depth studies revealed a competition between the polymer shrinkage caused by electrostatic attraction and shrinkage-resistance from the strong binding of the polymer with glycan molecules, which contributed to the varying extend of shrinkage of the graft polymer in nanochannels, and the different “OFF-ON” change in ion flux and the detectable current signals.

This work broadens the application of nanochannel systems in bioanalysis and biosensing, and opens a new route to glycan analysis, for example, the single-molecule analysis of complex glycan using single nanochannel/nanopore, that could help to uncover the mysterious and wonderful glycoworld.

According to the similar strategy, the group also designed and developed the Ca2+-self-controlled bioinspired Ca2+ nanochannels (NPG Asia Materials, 2019) and the cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP)-controlled ion nanochannels (J. Mater. B., 2019). These works further highlight the potential of biomolecule-responsive polymer for the construction of bioinspired ion nanochannels.

These works were supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, DICP Innovation Funding, and LiaoNing Revitalization Talents Program. It was dedicated to the 70th anniversary of DICP, CAS. (Text by LI Minmin Li, QING Guangyan)